Separation for parity games

This post discusses a framework for reducing parity games to safety games by the construction of an automaton.

There are three quasipolynomial time algorithms for parity games, namely the statistics games of Calude, Jain, Khoussainov, Li, and Stephan, the succinct progress measure algorithm of Jurdziński and Lazić, and the register games of Lehtinen.

The separating automata framework is due to Bojańczyk and Czerwiński, who worked out in their lecture notes An automata toolbox how to construct a separating automaton from the first algorithm. They use a slightly different notion of separating automata; the notion presented here is weaker (hence better), in the sense that a separating automaton here is also one for Bojańczyk and Czerwiński.

Some of the material presented in this paper is spelled out in full details in this paper. This post does not depend on the other ones but is a good introduction to the next one on universal graphs.

The separation approach

We fix $n,d$ two parameters.

We consider edge-labelled graphs: a graph is a structure with $d$ binary relations $E_i$ for $i \in [0,d-1]$, with $(v,v’) \in E_i$ meaning that there is an edge from $v$ to $v’$ labelled $i$. We write $(v,i,v’) \in E$ instead of $(v,v’) \in E_i$. We say that a graph has size $(n,d)$ if it has at most $n$ vertices and uses priorities in $[0,d-1]$.

We let $\Parity \subseteq [0,d-1]^\omega$ denote the set of infinite words such that the maximal priority appearing infinitely often is even.

We say that a graph satisfies parity if all paths in the graph satisfy the parity objective. Note that this is equivalent to asking whether all cycles are even, meaning the maximal priority appearing in the cycle is even.

The automata we consider are deterministic safety automata over infinite words on the alphabet $[0,d-1]$, where safety means that all states are accepting: a word is rejected if there exist no run for it.

In the following we say that a path in a graph is accepted or rejected by an automaton; this is an abuse of language since what the automaton reads is only the priorities of the corresponding path.

Definition: An automaton is \((n,d)\)-separating if the two following properties hold.

- For all graphs of size $(n,d)$ satisfying parity, the automaton accepts all paths in the graph

- All words accepted by the automaton are in parity

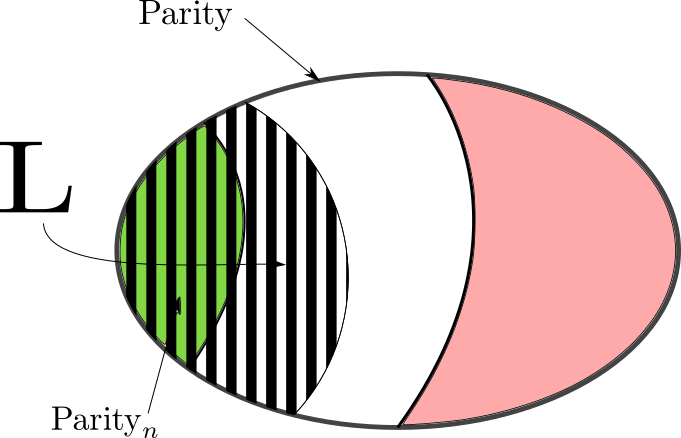

We let $\Parity_n$ denote the union over all graphs of size $(n,d)$ satisfying parity of their set of paths.

\[\Parity_n = \bigcup \set{ \text{Paths}(G) : G \text{ graph of size } (n,d) \text{ satisfying } \Parity}\]

The definition of separating automata can be summarised as follows, letting $L$ denote the language recognising by the automaton.

\[\Parity_n \subseteq L \subseteq \Parity\]The following lemma justifies the definition of separating automata.

Lemma: Let $L$ be the language recognised by a separating automaton. Then for all games with $n$ vertices and $d$ priorities, we have that Eve has a strategy ensuring $\Parity$ if and only she has a strategy ensuring $L$.

Proof: Let us first assume that Eve has a strategy $\sigma$ ensuring $\Parity$. It can be chosen positional. Then $G[\sigma]$, the graph obtained by restricting the game $G$ to the moves prescribed by $\sigma$, is a graph of size $(n,d)$ satisfying $\Parity$, so the automaton accepts all paths in $G[\sigma]$. In other words, all paths consistent with $\sigma$ are in $L$, or equivalently $\sigma$ ensures $L$.

Conversely, assume that Eve has a strategy $\sigma$ ensuring $L$. Since $L \subseteq \Parity$, the strategy $\sigma$ also ensures $\Parity$.

It follows that solving the parity game is equivalent to solving a safety game with $m \times |A|$ edges, where $m$ is the number of edges of $G$ and $|A|$ the number of states of the separating automaton. Since solving a safety game can be done in linear time in the number of edges, this gives an algorithm whose running time is linear in $m$ and $|A|$.

In the remainder of this post we discuss four solutions of the separation problem:

- the small progress measure of Jurdziński is a solution of the separation problem with $|A| = O(n^{\frac{d}{2}})$,

- the succinct progress measure of Jurdziński and Lazić is a solution of the separation problem with $|A| = O(n^{\log(d)})$,

- the statistics of Calude, Jain, Khoussainov, Li, and Stephan is a solution of the separation problem with $|A| = O(n^{\log(d)})$,

- in a weak sense the registers of Lehtinen is a solution of the separation problem with $|A| = O(n^{\log(d)})$.

The small progress measures

The fact that the small progress measures form a solution of the separation problem was essentially shown by Bernet, Janin, and Walukiewicz, in the paper Permissive strategies: from parity games to safety games. By essentially I mean that the separation problem is hinted at in the conclusion, but the definition of a separating automaton does not appear.

We construct a separating automaton. The states of the automaton are $d/2$-tuples of integers in $[0,n]$, they are numbered $1,3,\ldots,d-1$. For a tuple $x$ and a priority $p$, we let $x(p)$ denote the $p$ component of $x$. The initial state is the tuple containing only $0$, written $x_0$.

The transition function is as follows: from the tuple $x$, reading a vertex $v$ of priority $p$, the next tuple $x’$ is as follows:

- if $p$ is even, then the new tuple is the same as $x$, but all priorities smaller than $p$ are reset to $0$,

- if $p$ is odd, then the new tuple is the same as $x$, but the $p$ component is incremented by $1$ and all priorities smaller than $p$ are reset to $0$. If the $p$ component cannot be incremented (because it has value $n$), the automaton rejects.

Formally, the transition function is \(\delta : [0,n]^{\frac{d}{2}} \times [0,d-1] \to [0,n]^{\frac{d}{2}}\), inducing \(\delta : [0,d-1]^* \to [0,n]^{\frac{d}{2}}\). For a word $w$ and a tuple $x$, we let $\delta(x,w)$ denote the tuple reached after reading $w$ from $x$, if defined. Then, $\delta(w)$ is $\delta(x_0,w)$.

The automaton is safe: all states are accepting, and if a transition is undefined, the automaton rejects.

Lemma:

- $\Parity_n \subseteq L$

- $L \subseteq \Parity$

Proof: We start by proving the first item. It follows from the following invariant: for every $w \in [0,d-1]^*$ which is not rejected by the automaton, $w$ has a suffix of the form $w_{d-1} \cdots w_3 w_1$, where for $p \in \set{1,3,\ldots,d-1}$, the priority $p$ appears at least $\delta(w)(p)$ times, and no larger priority appears in $w_p$.

Assume the invariant holds for $w$, and we read a vertex $v$ of priority $p$, there are two cases:

- if $p$ is even, we construct the suffix $w_{d-1} \cdots (w_{p+1} v)$ of $w v$, i.e. the new word for $p+1$ is $w_{p+1} v$.

- if $p$ is odd, we construct the suffix $w_{d-1} \cdots (w_p v)$ of $w v$, i.e. the new word for $p$ is $w_{p+1} v$. The priority $p$ appears at least $\delta(wv)(p) = \delta(w)(p) + 1$ times.

This completes the proof of the invariant. Now, we argue that if a word is rejected by the automaton, then it contains an odd cycle, which is the contrapositive of the first item. Let $wv$ such that $w$ is accepted and $wv$ is rejected. Assume that $v$ has priority $p$, this implies that $\delta(w)(p) = n$. It follows that in $w_p w_{p-1} \cdots w_1 v$ the priority $p$ appears at least $n+1$ times, and no larger priority appears. Since there are $n$ vertices, some vertex repeats twice, forming an odd cycle.

We now prove the second item: it follows from the observation that if $w$ is a word of odd maximal priority $p$, then $x(p) < \delta(x,w)(p)$. Indeed, the $p$ component is either not touched when a lower priority is visited, or incremented. Consider now the largest priority appearing infinitely many times, and assume it is odd: the word consists of infinitely many paths with maximal odd priority $p$, and each of them induce an increase in the corresponding component, which eventually results in the automaton rejecting.

The succinct progress measures

The fact that the succinct progress measures form a solution of the separation problem is best explained using the notion of universal trees defined in this post.

Indeed, the succinct progress measures is nothing but the construction of a concrete universal tree, and there is a simple and natural construction of a separating automaton from any universal tree. We refer to the post on universal graphs for this construction.

The statistics

The construction of a separating automaton has been worked out by Bojańczyk and Czerwiński in their lecture notes An automata toolbox. They make the assumption that $n = d$, which can easily be lifted.

The registers

As explained in this paper one can construct some automaton, which we can used to obtain a separating automaton. However the automaton is non-deterministic, which means it does not fit the framework above. A better and cleaner way to understand this approach is to show that the automaton is good for small games; we refer to this paper for more details.