A robust class of sequences

We introduce a subclass of linear recurrence sequences (LRS). We show that this class is robust by giving several characterisations.

The results presented here are mostly due to Corentin Barloy, who took a summer internship in LaBRI, Bordeaux, under the supervision of Nathan Lhote, Filip Mazowiecki, Vincent Penelle, and myself.

01/10/2019: See the technical report A Robust Class of Linear Recurrence Sequences. The paper has been accepted to CSL’2020.

We consider sequences of rational numbers, as for instance the Fibonacci sequence \(0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,\ldots\)

Theorem: The following classes of sequences are equal

- sequences denoted by poly-rational expressions (Poly-Rat)

- sequences recognised by polynomially ambiguous weighted automata (Poly-WA)

- sequences recognised by copyless cost register automata (CCRA)

- sequences whose formal series are of the form $\frac{P}{Q}$ where $P,Q$ are rational polynomials and the roots of $Q$ are roots of rational numbers

- linear recurrent sequences (LRS) whose eigenvalues are roots of rational numbers

Poly-Rational expressions

We define a set of operators to denote sequences using expressions. We use two basic building blocks: arithmetic sequences and geometric sequences. For instance a geometric sequence is defined by

\[u_0 = a,\qquad u_{n+1} = \lambda \cdot u_n\]where $a,\lambda$ are rational numbers.

The operators are:

- $u + v$ is the component wise sum of sequences

- $u \cdot v$ is the component wise product of sequences

- the shift $(a,u) = (a,u_0,u_1,\ldots)$ with $a$ a rational number

- the shuffle $\langle u^1,u^2,\ldots,u^k \rangle = (u^1_0,u^2_0,\ldots,u^k_0,u^1_1,u^2_1,\ldots,u^k_1,u^1_2,\ldots)$

We let Poly-Rat be the class of sequences denoted by rational expressions, in other words the smallest class of sequences containing arithmetic and geometric sequences and closed under sum, product, shift, and shuffle.

Polynomially ambiguous weighted automata

We consider weighted automata for the semiring $(\Q,+,\times)$ over a one-letter alphabet.

The ambiguity of an automaton is the function which associates with $n$ the number of accepting runs of $a^n$. An automaton is said to be polynomially ambiguous if its ambiguity is bounded by a polynomial. We let Poly-WA be the set of sequences computed by polynomially ambiguous weighted automata.

Theorem: Poly-Rat = Poly-WA

Most of the remainder of this blog post sketches a proof of this (non-trivial) equivalence.

Poly-Rat $\subseteq$ Poly-WA

This inclusion is rather easy, it requires to prove the closure of Poly-WA under sum (union of automata), product (product of automata), shift (adding a new initial state), and shuffle (multiplying by $\{1,\ldots,k\}$).

Poly-WA $\subseteq$ Poly-Rat

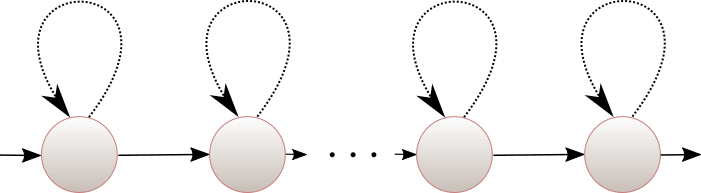

The first step is to decompose polynomially ambiguous automata into some normal form called chained loop. An automaton is a chained loop if it has the shape depicted in the figure below. Note that in particular it has a unique initial state and a unique final state. The loops can have arbitrary lengths but they are disjoint from one another.

Lemma: Any polynomially ambiguous weighted automaton is equivalent to a union of chained loops.

We skip the proof of this lemma. The crux is that in a polynomially ambiguous automaton there cannot be two nested loops. Hence an automaton is the union of all the chained loops it contains.

Two chained loops can be concatenated and this forms another chained loop. This way, a chained loop can be seen as a concatenation of one-state automata. At this point is it convenient for reasoning to use formal series, which are (in our setting) functions from $\N$ to $\Q$. We represent them as a sum $\sum_n a_n X^n$, and use two operations on them: addition and Cauchy product.

Here are some key observations:

- one-state automata exactly recognise formal series of the form $\frac{\alpha}{1 - \lambda X}$, where $\alpha$ is the product of the initial and the final weight and $\lambda$ the product of the weights in the loop,

- concatenation of chained loops corresponds to Cauchy products of their formal series,

- union of automata corresponds to sums of their formal series.

To conclude the proof of the theorem, meaning the inclusion Poly-WA $\subseteq$ Poly-Rat, it would be enough to prove that every sequence whose formal series is of the form $\frac{\alpha}{1-\lambda X}$ belongs to Poly-Rat, and that the class of formal series corresponding to sequences in Poly-Rat is closed under sum and Cauchy product. Unfortunately, the closure under Cauchy products is not clear.

We sidestep this issue by observing that here we only do Cauchy products of formal series of the form $\frac{\alpha}{1-\lambda X}$.

Lemma: Cauchy products of formal series of the form $\frac{\alpha}{1-\lambda X}$ are of the form sums of $\frac{P}{(1 - \lambda X^k)^N}$ for $P$ a rational polynomial.

We skip the proof of this lemma. The crux is to observe that $\frac{1}{PQ}$ for $P,Q$ two polynomials can be written as $\frac{A}{P} + \frac{B}{Q}$ for $A,B$ two polynomials, which follows from the fact that $\Q[X]$ has Euclidian division.

We conclude. First, one can reduce to the case $\frac{1}{(1 - \lambda X^k)^N}$ using shifts. Now

\[\frac{1}{(1 - \lambda X^k)^N} = \sum_{n \ge 0} \binom{n + N - 1}{N} \lambda^n X^{k \cdot n}\]Note that $\binom{n + N - 1}{N}$ is a polynomial in $n$ of degree at most $N$, i.e. $\binom{n + N - 1}{N} = \sum_{p = 0}^N a_p n^p$. It follows that

\[\frac{1}{(1 - \lambda X^k)^N} = \sum_{p = 0}^N\ a_p \cdot \sum_{n \ge 0} n^p \lambda^n X^{k \cdot n}\]It is then enough to prove that for each $p$ the sequence whose formal series is

\[\sum_{n \ge 0} n^p \lambda^n X^{k \cdot n}\]is in Poly-Rat. We leave this last (easy) step to the reader.

From there one easily obtains the other two characterisations in terms of formal series or linear recurrent sequences whose eigenvalues are roots of rational numbers.

Application: the Fibonacci sequence

Theorem: Fibonacci is not in Poly-WA, implying that Poly-WA is a strict subclass of WA.

To see this, observe that the formal series associated with the Fibonacci sequence is

\[\frac{X}{1-X-X^2}\]Thanks to that, we know that this sequence is not in Poly-WA. Assume for the sake of contradiction that it is, then the formal series above would be written as sums of $\frac{P}{(1 - \lambda X^k)^N}$. Since $\varphi^{-1}$ (the inverse of the golden ratio) is a pole, it would be the root of some $1 - \lambda X^k$, which cannot be the case.

Cost register automata

CRA are deterministic automata with write-only registers. Each transition updates the registers using addition and multiplication. <!– Here is an example of a CRA over the alphabet ${a,b}$ computing the product of the number of $a$ and the number of $b$.

–> A CRA is said to be copyless if in each update, each register is used at most once.

We let CCRA denote the class of sequences computed by copyless cost register automata over a one-letter alphabet.

Theorem: CCRA = Poly-Rat

Both inclusions are not too hard to show although they require some technical care.