The fundamental theorem of parity games

This post proves a very important theorem about parity games, showing the interplay with (universal) trees.

The goal of this post is to prove the following result. This is the key technical point of a recent joint work with Thomas Colcombet proving that separating automata (see the corresponding post) have at least quasipolynomial size.

This theorem is an elaboration of the classical result about signature assignments or progress measures being witnesses of positional winning strategies in parity games (see e.g. the small progress measure treatment). The novelty here is to phrase this theorem using graph homomorphisms and universal trees, and giving a different argument using saturation.

Theorem: Let $G$ be a graph and $T$ a universal tree. The following statements are equivalent:

- $G$ satisfies parity

- there exists a tree $t$ and a homomorphism $\phi : G \to t$

- there exists a homomorphism $\psi : G \to T$

This result is interesting on its own. For instance, it is the basis ingredient of the value iteration algorithm (see the corresponding post).

We refer to this technical report for full details.

Graphs

We fix $n,d$ two parameters.

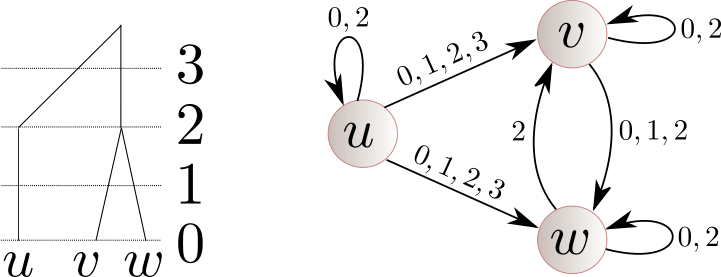

We consider edge-labelled graphs: a graph is a structure with $d$ binary relations $E_i$ for $i \in [0,d-1]$, with $(v,v’) \in E_i$ meaning that there is an edge from $v$ to $v’$ labelled $i$. We write $(v,i,v’) \in E$ instead of $(v,v’) \in E_i$. The size of a graph is its number of vertices.

A graph homomorphism is simply a homomorphism of such structures: for two graphs $G,G’$, a homomorphism $\phi : G \to G’$ maps the vertices of $G$ to the vertices of $G’$ such that

\[(v,i,v') \in E \ \implies\ (\phi(v),i,\phi(v')) \in E\]As a simple example that will be useful later on, note that if $G’$ is a super graph of $G$, meaning they have the same domain and every edge in $G$ is also in $G’$, then the identity is a homomorphism $G \to G’$.

We let $\Parity \subseteq [0,d-1]^\omega$ denote the set of infinite words such that the maximal priority appearing infinitely often is even.

A path is a sequence of triples $(v,i,v’)$ in $E$ such that the third component of a triple in the sequence matches the first component of the next triple. (As a special case we also have empty paths consisting of only one vertex.) For a path $\rho$ we write $\pi(\rho)$ for its projection over the priorities, meaning the induced sequence of priorities.

We say that a graph satisfies parity if all paths in the graph satisfy the parity objective. Note that this is equivalent to asking whether all cycles are even, meaning the maximal priority appearing in the cycle is even.

The outline is as follows.

- we first explain how to relate trees and graphs,

- we prove the fundamental theorem for parity games.

From trees to graphs to trees

This part is a bit technical but necessary. It explains how we can see trees as graphs with some properties.

In this context we label the levels of a tree by priorities from bottom to top. More precisely, even priorities sit on levels corresponding to nodes, and odd priorities inbetween levels.

We first explain how a tree induces a graph. Let $T$ be a tree, we construct a graph $G(T)$ whose vertices are the leaves of $T$ and such that $(v,i,v’) \in E$ if

- for $i$ even, the ancestor of $v$ at level $i$ is to the left of or equal to the ancestor of $v’$ at level $i$

- for $i$ odd, we rely on the previous item: if $(v,i-1,v’) \in E$ and $(v’,i-1,v) \notin E$

Fact: For $t,T$ two trees, the following are equivalent.

- $t$ embeds in $T$

- there exists a homomorphism $\phi : G(t) \to G(T)$

We define the converse transformation. We say that a graph satisfying the following four properties is tree-like.

- if $(v,i,v’) \in E$ and $(v’,j,v’’) \in E$, then $(v,\max(i,j),v’’) \in E$

- for $i$ even, $E_i$ is total: either $(v,i,v’) \in E$ or $(v’,i,v) \in E$ (possibly both)

- for $i$ even, $E_i$ is reflexive: $(v,i,v) \in E$

- for $i$ odd, $(v,i,v’) \in E$ if and only if $(v,i-1,v’) \in E$ and $(v’,i-1,v) \notin E$

Note that the first item implies that $E_i$ is transitive and the second and third items imply that $E_0 \subseteq E_2 \subseteq \cdots \subseteq E_{d-1}$. Further, for $i$ odd $E_i$ is non-reflexive.

Let $G$ be a tree-like graph, we construct a tree $T(G)$ whose leaves are the vertices of $G$. For $i$ even, the nodes at level $i$ are the equivalence classes of vertices for the total preorder $E_i$.

Fact: Let $t$ be a tree, then $G(t)$ is tree-like, and $T(G(t)) = t$.

We identify trees and tree-like graphs through the two reciprocal transformations described above. Hence we see trees as special graphs.

Fundamental theorem

We are now ready to prove the main theorem.

Note that since a tree is a tree-like graph, by homomorphism from a graph to a tree we mean homorphisms from a graph to a tree-like graph, which are structures over the same signature.

For the implication $1 \implies 2$ we introduce maximal graphs satisfying parity. We say that a graph $G$ is a maximal graph satisfying parity if adding any edge to $G$ would introduce an odd cycle.

Lemma: A maximal graph satisfying parity is tree-like.

Proof: Let $G$ be a maximal graph satisfying parity. We need to show that $G$ satisfies the following properties.

- if $(v,i,v’) \in E$ and $(v’,j,v’’) \in E$, then $(v,\max(i,j),v’’) \in E$

- for $i$ even, $E_i$ is total: either $(v,i,v’) \in E$ or $(v’,i,v) \in E$ (possibly both)

- for $i$ even, $E_i$ is reflexive: $(v,i,v) \in E$

- for $i$ odd, $(v,i,v’) \in E$ if and only if $(v,i-1,v’) \in E$ and $(v’,i-1,v) \notin E$

For the first item, if adding $(v,\max(i,j),v’’) \in E$ would create an odd cycle, then replacing the edge by the two consecutive edges $(v,i,v’) \in E$ and $(v’,j,v’’) \in E$ would yield an odd cycle, contradiction.

For the second item, if we do not have $(v,i,v’) \in E$ then there exists a path from $v’$ to $v$ with maximal priority odd and larger than $i$, and similarly for $(v’,i,v) \in E$. If both cases would occur, this would induce an odd cycle.

The third and fourth items are clear.

We now rely on the above Lemma to prove the implication $1 \implies 2$. Consider a graph $G$ satisfying parity, we construct a maximal graph $t$ satisfying parity by starting from $G$ and throwing in new edges as long as the graph satisfies parity. We say that $t$ is a saturation of $G$, it is by construction a super graph of $G$ hence $G$ maps homomorphically into $t$. Thanks to the Lemma above, $t$ is a tree.

The implication $2 \implies 3$ is obtained by composing homomorphisms: indeed, since $T$ is universal there exists a homomorphism $\phi’ : t \to T$, which yields a homomorphism $\phi’ \circ \phi : G \to T$.

The implication $3 \implies 1$ is given by the following lemma.

Lemma: Let $G$ be a graph such that there exists a tree $t$ and a homomorphism $\phi : G \to t$, then $G$ satisfies parity.

Proof: We consider a loop in $G$.

\[(v_1, i_1, v_2) (v_2, i_2, v_3) \cdots (v_k, i_k, v_1)\]Let us assume towards contradiction that its maximal priority is odd and without loss of generality it is $i_1$. Applying the homomorphism $\phi$ we have

\[(\phi(v_1),i_1,\phi(v_2)) \in E,\ (\phi(v_2),i_2,\phi(v_3)) \in E,\ \ldots, \ (\phi(v_k),i_k,\phi(v_1)) \in E\]We obtain thanks to the first property of trees that $(\phi(v_1),i_1,\phi(v_1)) \in E$, which contradicts that for $i$ odd $E_i$ is non-reflexive.

In the next post we rely on this theorem to prove a lower bound on the size of separating automata.